Chino Valley Ranchers organic laying houses in Idalou, Texas, certified by CCOF

Industry Watchdog Files Formal Legal Complaint Against Largest Certifier

LA FARGE, WIS. — In the 1970s and 80s, as organic farming grew in the United States and became commercialized, farmers who had to charge a premium for organic food saw the need to create consumer confidence by founding a number of independent certifying agencies. After Congress passed the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990, it charged the USDA with the oversight of dozens of certifiers to ensure their independence and the harmonization of standards.

An industry watchdog, OrganicEye, has requested the USDA Office of Inspector General (OIG) investigate the National Organic Program, alleging malfeasance in its lack of preventing corporate influence peddling in the form of financial payments to certifiers over and above inspection fees, leading to the erosion of the integrity of the organic label.

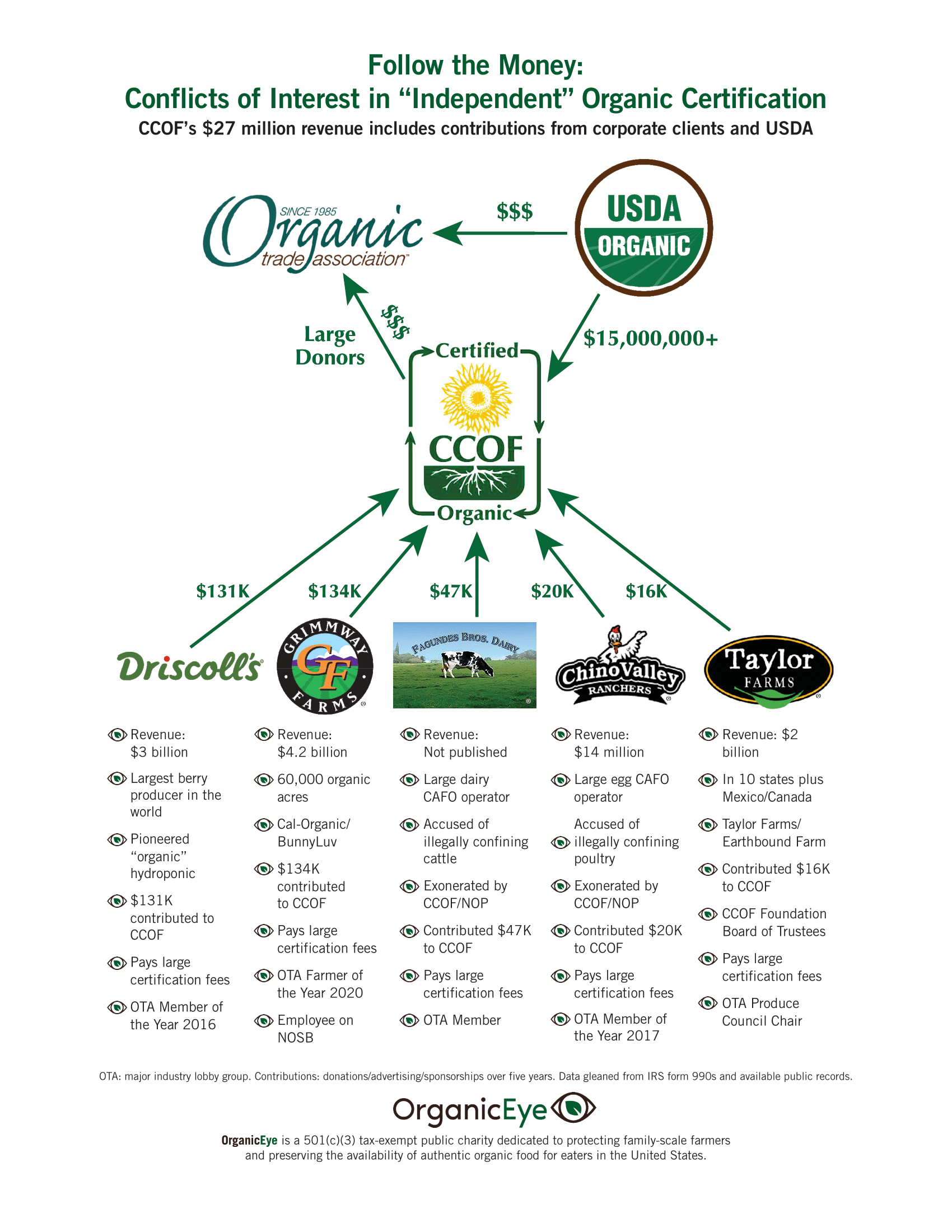

In addition to the requested investigation of federal organic regulators, OrganicEye has filed a formal legal complaint against the nation’s largest certifier, CCOF, based in Santa Cruz, California, documenting hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of contributions, advertising purchases, conference sponsorships, and other payments over and above certification fees.

“It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to refer to the extraordinary amount of money changing hands between agribusinesses clients and the profiting organizations that certify them, as ‘payola,’” said Mark Kastel, OrganicEye’s Executive Director.

USDA regulations require nonprofits doing lobbying, advocacy work, and education to divest themselves of their certification operations so competing activities do not constitute a conflict of interest. OrganicEye’s research has found that some certifiers’ nonprofits have either remained as a single corporate entity or have separated conflicting functions solely on paper.

“The optics are terrible,” said Kastel. “In a number of cases, you’ve had major corporations involved in alleged improprieties that appear to have purchased a get-out-of-jail-free card through their substantial largess in contributions to CCOF and other certifiers.”

As an example, CCOF, the country’s largest certifier with revenues of $27 million a year — and the subject of the legal complaint filed by OrganicEye — certifies Driscoll’s, the largest berry producer in the world with annual revenues of $3 billion.

Although statutory and regulatory language requires careful soil stewardship before a farm can be certified as organic under the USDA program, Driscoll’s, along with the industry’s primary lobby group, the Organic Trade Association (OTA), spearheaded a stealthy effort that resulted in regulators allowing hydroponic (soilless production) certification as organic, leaving authentic organic farmers challenged to compete.

“When I was president of the CCOF Board of Directors in the 1980s, the entire leadership was made up of family farmers who were dedicated to creating and preserving a true alternative to industrial agriculture and all the collateral damage it was doing to the environment and human health,” said Warren Weber, a longtime organic farmer from Bolinas, California.

Weber left CCOF to help form a separate and more local certification organization in Marin County, California, after corporate agribusiness began influencing his former certifier.

Although CCOF is split into three separate corporate entities, including a limited liability corporation performing its certification work, all staff are located in the same offices and report to the same CEO, with many interlocking relationships in leadership on the respective boards.

Rather than exclusive family farm leadership, over half of the CCOF board members are now from agribusinesses with annual revenues ranging from 1.3 to over 100 million dollars, according to OrganicEye. One has revenue of over $1 billion. “That kind of leadership can lead to the betrayal of the family farmers and their customers, who represent most of the CCOF-certified clients,” added Weber.

Over a five-year period, CCOF has received more than $130,000 of largess from Driscoll’s, over and above the substantial fees paid for certification.

Along with hydroponics (what Driscoll’s refers to as “container growing”), CCOF and other large certifiers are granting organic status to large livestock factories (concentrated animal feeding operations — CAFOs) which have long been accused of skirting the organic regulations.

“I filed a complaint with the USDA after I witnessed one of CCOF’s clients, Fagundes Brothers Dairy, confining their cattle to feedlots when the law was clear that organic cows had to have access to pasture,” said OrganicEye’s Kastel.

The spring Kastel visited the dairy, the weather and pasture growth permitted other organic dairy farms in the Central Valley to have their cattle out on pasture, he said. During two subsequent visits to the Fagundes operation by other local certified organic farmers, the total confinement of animals and harvesting of the “pasture” as first cutting stored hay instead of grazing was documented with photographs.

Despite the evidence presented, the USDA delegated the enforcement to CCOF — which refused to take any enforcement action.

According to OrganicEye’s Kastel, “With the USDA delegating so much authority to certifiers, there are now effectively two organic labels: corporate brands affiliated with the OTA and certified by organizations motivated by profit and industry growth, and other industry participants who have not lost touch with the foundational precepts of the organic movement.”

OrganicEye is assisting farmers around the country who are either switching to certifiers who share their values or, at a minimum, giving their current certifiers a one-year ultimatum to implement moratoriums on certifying hydroponics and CAFOs and notify existing clients that they will not certify them in the future.

“Like many other longtime organic farmers, I’m certainly focused on making a living through my craft. But my family and I are doing this hard work, producing superior food, because our hearts are in it,” said Hansel Kern, an organic fresh market vegetable producer from North Fork, California. “The fourth generation on this farm is just as emotionally motivated as I am, and we are going to make sure that our certifier doesn’t betray our values and endanger the credibility of the organic movement.”

-30-

MORE:

The Long Tentacles of Big Ag in Organics

For more information on CCOF’s finances and conflicts of interest, please see OrganicEye’s backgrounder.

For an in-depth look at their two largest donors/certification clients, please see OrganicEye’s dossiers on Driscoll’s and Grimmway Farms.

Access the spreadsheet containing a comprehensive listing of donors to CCOF here.

Chino Valley: A few years ago, Kastel hired an aerial photography team to fly over “organic” CAFOs in various states. The majority had their livestock entirely confined. One dairy had a total of about 10% of their cattle on pasture. No chickens were outdoors in either egg-laying operations or buildings housing broilers for meat production.

The investigation included one operation owned by Chino Valley Ranchers in Texas. Like the Fagundes dairy, Chino Valley operates a number of conventional and organic CAFOs. In conflict with the law, no chickens (zero) were outdoors, despite ideal conditions for livestock (as confirmed with the National Weather Service) in an area where the heat would sometimes justify temporary confinement.

Just as in the Fagundes case, no enforcement action was taken by the USDA or CCOF, despite well-documented conditions that conflicted with the federal organic standards.

In addition to accepting sizable donations from corporations and individuals receiving certification from CCOF, the organization also accepts donations from a number of suppliers of fertilizer and other farm inputs that must be scrutinized for their appropriateness for use in organic production.

OrganicEye’s Kastel has long been critical of the USDA’s National Organic Program for allowing “independent” certifiers to effectively act as lobbyists for their corporate clients.

According to Kastel, they regularly testify at National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) meetings in defense of the use of synthetic and non-organic materials in organic agriculture and food processing.

“I have contended that the certifiers should act as impartial referees rather than advocating on behalf of their paying clients,” said Kastel.

In many cases, the certifiers have shielded agribusinesses from criticism of their continued use of what OrganicEye describes as inappropriate ingredients in organic food production. “Some, like carrageenan and specially-bred conventional celery powder used as a source of sodium nitrate, are documented to be potential or likely carcinogens,” Kastel added.

He said that no certifier has been more active in either having employees serve on the NOSB or lobbying its members than CCOF.

OrganicEye is encouraging organic farmers to switch to one of the high-integrity certifiers, including: Organic Crop Improvement Association (OCIA), OneCert, Global Organic Alliance (GAO), NOFA-NY, Vermont Organic Farmers, and Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA). [Certified organic producers can contact OrganicEye for a free consultation.]

In addition to CCOF, other certifiers that certify hydroponic and/or livestock CAFOs include: the Texas and Colorado Departments of Agriculture, Quality Assurance International (QAI), Oregon Tilth (OTCO), Organic Certifiers, Inc., Quality Certification Services (QCS), EcoCert, Where Food Comes From Organic (WFCFO, formerly A Bee Organic), and Midwest Organic Services Association (MOSA).